Global Collectives

Collectives: The Models for Success with Studio Manifold (London, England) and Kansas City Urban Potters, (Kansas City, USA.).

How have collectives become the current business model for success? We have seen the success of collectives with the Guerilla Girls (1985), the influential feminist artists pressing to change the gender and political inequalities that continue to dominate Western culture, and Marcel Dzama, founder of the Royal Art Lodge (1996), who devised collaborative drawing events that helped bring the medium back into the center stage of high art. These artists helped to bring the model of contemporary collectives back to the mainstream. Craft artists are simultaneously joining the ranks of these established collectives, by stepping outside of the traditional studio model and singular creative visions to engage and interact with national and global public communities.

Embracing the global collective mentality, we visit two groups that are already reaching impressive levels of achievement. London-based Studio Manifold’s work spans beyond the dialogs between craft, digital technologies, and sculpture. Its members have been recipients of the prestigious Jerwood Makers Award and have participated as ceramic artists in residence at the Victoria and Albert Museum in the UK. In the US, members of the Kansas City Urban Potters are researching and re-contextualizing the role of traditional pottery and social engagement. Having raised capital for their start-up through crowdfunding and arts organizational initiatives, they are now an established LLC with an art gallery, studios, and a growing educational clay center in the heart of Kansas City.

Counterculture

Ceramics of Tom Bartel

Reds, baby blues, yellows, and black; textured surfaces showcasing dots turning into polka dots; single lines turning into stripes. Magical, mysterious, and frequently gritty, these fragmented figures stand firm, embedded with broken, cracked lines that suggest a sense of experiences and the notion of implied time. The intriguing and transgressive ceramics of Tom Bartel are fueled by a combination of fine art, historical, and contemporary themes, reminding us of the ontology of humanity. His works reflect a depth of art historical knowledge, thoughtfully and attentively considered in a world of overbearing visual clutter, exploring many cultural references through reconceptualization.

Tom Bartel has been working in sculptural ceramics for more than 20 years. In his formative years, growing up in Cleveland, Ohio, Bartel took inspiration from his childhood experiences, as well as some unexpected places. As he roamed his home town, he brought to life the architecture that surrounded him, the breaks in the façades of buildings, the cracks on the concrete beneath his feet, recognizing the ability of a city to hold its history and capture time within its broken surfaces.

His fascination with the architectural landscape brings to mind the work of Gordon Matta-Clark, an artist for whom the cityscape provided creative fuel for an ongoing internal dialog, a means to communicate time and decay through frequently abandoned and invisible architecture, recomposing them into art. Tom Bartel says, “In this time and place, I grew up surrounded by decay. I think the interesting part of this is how it eventually clarified that my aesthetic originated from an early age. I am enamored with heavily worn and rustic surfaces. I find them to be rich and beautiful. I intend them to also perform as evidence of or a record for (signifying) how something has changed over time or how something has been affected by the elements and or time.”

Crowdfunding for Artists

Crowdfunding for Artist | Ceramic Monthly Magazine

Beth Cavener and Kelsey Bowen

Funding in the arts is a constant topic of discussion for many, especially for individual artists, independent galleries, museums, and community art centers. Even though a rare few are self funded, most organizations are in constant need of funding to cover operating costs, artistic programming, and educational initiatives. With such limited resources, how are individual artists expected to fund their own artistic practices?

Exploring alternative sources of funding is on a steady increase, and I find that crowdfunding is on the rise, helping established and emerging artists to continue to survive and thrive in their studios. Artists are turning to peer-to-peer supported online resources such as Hatchfund (www.hatchfund.org), Indiegogo (https://entrepreneur. indiegogo.com), Patreon (www.patreon.com), Kickstarter (www. kickstarter.com), You Caring (www.youcaring.com), Fundly (https://fundly.com), Just Giving (www.justgiving.com), and Facebook (www.facebook.com).

I interviewed internationally recognized ceramic artist Beth Cavener and ceramic artist and recent graduate Kelsey Bowen on their own unique experiences with successfully raising funds using online crowdfunding platforms.

Beth Cavener

Cavener has successfully funded two large-scale projects; one in partnership with United States Artists (USA) and the other, a self-directed funding initiative to support her volunteer-based internship…

Behind the Hidden Hare

Russell Wrankle | Ceramics Monthly Magazine

Growing up in Southern California, Russell Wrankle spent his formative years wandering throughout the dusty Californian landscape. He could frequently be found exploring and observing the wilderness; a hunter at heart, he was always ready to catch his next jackrabbit.

Wrankle grew up in an untamed wildness. Both inside and outside his home he lived with the dominating force of hunter versus prey for the majority of his youth. As a twelve-year-old boy, he sought and found comfort in the stillness and silence of the wilderness. Falling in love with the serenity he found solace in hunting, catching, and skinning local jackrabbits with the intention of selling the skins, even though most of the time he simply ended up tucking the skins away at home, a process that was to reap rewards later on.

These hunting experiences gave Wrankle an edge, with a piece of insider knowledge and an in-depth understanding of just how real skin moves and responds to touching, ripping, pulling, and draping. With all the tangible tools he recalls as learning with his hands, he is now able to apply them to his barbarous and beastly charged contemporary sculptural works.

London Blue

Clay Culture: London’s Famous Blue Plaques

Ceramics Monthly Magazine

London’s famous blue ceramic plaques link the people of the past with the buildings of the present. Run by English Heritage, the Blue Plaques program celebrates its 150th anniversary this year.

English Heritage is a London-based organization that oversees more than 400 historical buildings, monuments, and heritage sites in the United Kingdom, including such extraordinary sites such as Stonehenge and Hadrian’s Wall, and an impressive 58 prehistoric sites, 66 castles, 53 Roman sites, 23 historical gardens, 7 palaces, and 3 medieval villages, among others!One of their longest running and most successful programs is London’s Blue Plaques. English Heritage’s objective is to ensure that places and spaces reveal their historical significance to a contemporary audience.

As a visitor, tourist, or resident taking a stroll through the city, you might casually stumble upon one of these deftly created blue ceramic plaques placed throughout the city of London. What are these plaques? Where do they come from? And, what do they mean?

The Figure as a

Map

to Human Experience

Ceramics: Art and Perception Magazine

FIGURATIVE ASSOCIATION: THE HUMAN FORM

Guest Symposium Writer and Closing Speaker

Author of The Figure as a Map to Human Experience

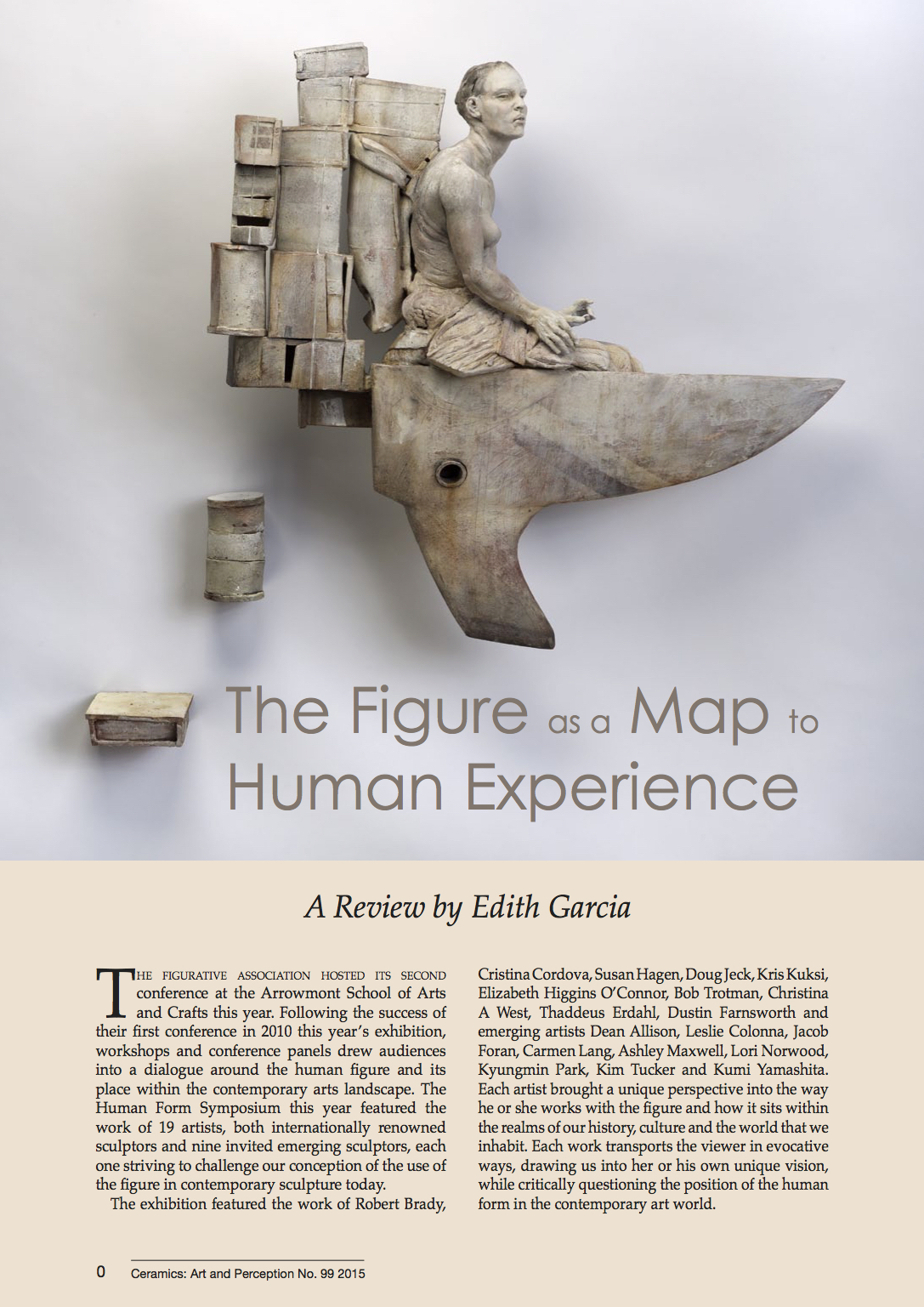

The figurative association hosted its second conference at the Arrowmont School of Arts and Crafts this year. Following the success of their first conference in 2010 this year’s exhibition, workshops, and conference panels drew audiences into a dialogue around the human figure and its place within the contemporary arts landscape. The Human Form Symposium this year featured the work of 19 artists, both internationally renowned sculptors and nine invited emerging sculptors, each one striving to challenge our conception of the use of the figure in contemporary sculpture today.

The exhibition featured the work of Robert Brady, Cristina Cordova, Susan Hagen, Doug Jeck, Kris Kuksi, Elizabeth Higgins O’Connor, Bob Trotman, Christina A West, Thaddeus Erdahl, Dustin Farnsworth, and emerging artists Dean Allison, Leslie Colonna, Jacob Foran, Carmen Lang, Ashley Maxwell, Lori Norwood, Kyungmin Park, Kim Tucker, and Kumi Yamashita. Each artist brought a unique perspective into the way he or she works with the figure and how it sits within the realms of our history, culture, and the world that we inhabit. Each work transports the viewer in evocative ways, drawing us into her or his own unique vision, while critically questioning the position of the human form in the contemporary art world.

Author of Ceramics and the Human Figure

An inside look into 40 international artists and their approach to working with the human figure and clay.

Representation of the human form through artistic expression has always existed in clay form, and it continues to evolve today. From exploring the whole figure, through fragmentation to the use of the body as a means to create, artists today are working with clay and the human form in very unconventional ways across the globe. Contemporary artists have learned to play with the possibilities of materials and form more so than ever before, with digital technologies enabling and enhancing the creative process.

This publication features works by key ceramic artists that work within the realm of the human form, showcasing and discussing individual artists with practices within the field of installation and sculpture as well as those incorporating new technologies. The artists are divided by themes, with each chapter giving a short introduction, and then going on to display the work and ideas of each, showing the large variety of work being made today. A chapter is also included on making methods, giving making sequences of the more innovative and challenging methods used by some of these artists.

VJ | Audio-Visual Art + VJ Culture

Edited by D-Fuse/Michael Faulkner/Edith Garcia/& others.

A major change has taken place at dance clubs worldwide: the advent of the VJ. Once the term denoted the presenter who introduced music videos on MTV, but now it defines an artist who creates and mixes video, live and in sync to music, whether at dance clubs and raves or art galleries and festivals. This book is an in-depth look at the artists at the forefront of this dynamic audio-visual experience.

Crucially, it combines how-to, showcase and reference elements. It opens with a series of articles on contextual and historical issues. The central section showcases the work of over 120 international VJs and the last chapter covers equipment (hardware and software) and typical stage set-ups (explaining installing equipment, utilizing space, creating an environment to suit an audience, etc..), along with supplementary guidelines and tips on how to make a performance.

The head is thinking

the body

Ceramics: Art and Perception Magazine

David Jones

Nature seems to have endowed man alone with this organ, (the hand) so that he is enabled to form a concept of a body by touching it on all sides. (1)

Edith Garcia leaves deliberate omissions, or ‘gaps’ in her work; these are points of incompleteness where the viewer has to finish the piece themselves. Marcel Duchamp, when talking about the nature of creativity, draws attention to the ‘art coefficient’ which refers to: the subjective mechanism which produces art in a raw state . . . in the chain of reactions accompanying the creative act, a link is missing. This gap which represents the difference between what he intended to realise and what he did realise, is the personal ‘art coefficient’ contained in the work...It is like an arithmetical relation between the unexpressed but intended and the unintentionally expressed . . . the spectator adds his contribution to the creative act. (2)

Garcia is well known for a highly polished range of post-modern ceramics that deals with implied answers to confrontational personal questions that are suggested rather than clearly articulated. She describes these autobiographical objects in terms that appear on the surface to be an antimony (a contradiction in terms) ‘happy, ugly scars’. They are statements in ceramics of earlier pains and complexes.

Born in Los Angeles she moved around the American Southwest with her parents and then to study; her practice has developed as both local and nomadic and within a tradition as well as outside and opposed to it. There has developed a strong avour of Mexico in her sculptures. The wall piece, Happy, ugly, scars which I saw most recently installed in the Museum of Modern Art in Tampa, Florida, where it had been selected for the NCECA (National Council on Education for the Ceramic Arts) exhibition was strangely reminiscent of the Day of the Dead manifestations in its half-entertaining/half-frightening elements that seem to add up to a narrative, suggesting both humour and fear in equal measure.

Characters from the narrative of her past appear as actors in her theatre of dreams and, while she was not actually raised as a Catholic, the incense of mythic ritual hangs around the work in an insubstantial cloud. She wanted to move away from what she refers to as this “quite stiff narrative work” and move towards a more expressive language – this is the new story (of the journey of her Master of Philosophy degree in ceramics at the Royal College of Arts in London, where she has been living for the past seven years). Thus, suddenly, she has presented a group of pieces that seem not to relate at all to the previous work; but we can read them as another sort of Duchampian ‘gap’: this time a kind of incompleteness in the making and fashioning process of the form. It is a re-examination of the materialty and the traditions of process-oriented making and forming.

In the MK Gallery in Milton Keynes, UK (alongside a solo retrospective of Andrew Lord, the English ceramics artist who, incidentally, has moved in the opposite direction and who has been resident in the US for most of his life) she is showing work that appears to be a complete discontinuity. The objects suddenly reference the muddy materiality of clay. They are recognizable as heads but only tangentially. They are as much about the soft malleability of the medium; a contrary turn to the direction that she has exploited in clay for so long, through its ability to take precise form. This new work is another reverie made manifest. They emanate from a ‘dream time’ of Olmec heads, the dry, harsh world of Pre-Columbian South America re-memorized within the green leaness of England’s capital city. They are profoundly tactile objects; Merleau-Ponty underlines the importance of ‘the felt’, signalling its complementary association with the visual:

There are tactile phenomena, alleged tactile qualities, like roughness and smoothness, which disappear completely if the exploratory movement is eliminated. Movement and time are not only an objective condition of knowing touch, but a phenomenal component of tactile data. They bring about the patterning of tactile phenomena, just as light shows up the conguration of a visible surface. (3)

The Olmec heads stand in the exhibition as mythical constructs that inhabit a liminal world between here and there – a strange past reimagined for today. These giant heads appear as from an extinct civilization; they remind us also (indeed almost anagrammatically) of the Golem (the great gure fashioned of clay in the ghettos of ‘Mitteleurope’) who was to rescue the Jewish people from successive waves of pogroms.

Garcia's heads are half-formed/ half-suggested, waiting to be re-animated for some unspecied trial or purpose. Despite her intentional referencing of the colossal pre-Hispanic objects, the actual pieces in the exhibition are but just a few orders greater than life-size. Yet they are nonetheless uncomfortably large and clearly wishing to assert a sculptural intent rather than the strange (almost domestic) scale of the elements within the previous installations. It is rather in the unfinished appearance of the work that they attempt to assert themselves and here that they also appear for what they are (Garcia herself talks about them as “a work in process”) suggesting a new beginning and intentionally unresolved as a result. It represents her evolution of a new visual and haptic language that, through the new-found tactility, is stretching out to new conversations through a deliberate eschewing of skill in the creation of these inchoate forms. It is pushing into new, yet uncharted, territories towards what Edith Garcia refers to as “The absence and presence of the human form in sculpture”.

Footnotes

1. Kant, I. quoted in Jacques Derrida, On Touching, Stanford University Press, 2005. p42.

2. Duchamp, M. (ed. Sanouillet, M. and Peterson, E.), 1973, The Writings of Marcel Duchamp, New York, Da Capo Press. p139. 3. Maurice Merleau-Ponty, The Phenomenology of Perception, London, Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1970. p. 315.

David Jones is a potter and writer. He is an academic, teaching at the University of Wolverhampton, UK. He is the author of Raku – Investigations into Fire and Firing - Philosophies within contemporary ceramic practice.